Introduction

When people talk about water quality, they often focus on clarity or colour, but lake nutrients quietly shape almost everything that happens below the surface. A modest increase in nutrient loading can be the difference between a clear, oxygen‑rich reservoir and one that drifts into chronic eutrophication with recurring algal blooms.

For drinking water managers, understanding lake nutrients is not just an academic exercise. It is directly connected to treatment costs, taste and odour episodes, and the long‑term security of supply. In this article we look at a practical eutrophication definition, how the phosphorus cycle works in lakes, and how monitoring and ultrasound‑based control can help keep reservoirs on a healthier path. For a concise overview of how nutrient enrichment alters lakes, see the summary from USGS on nutrients and eutrophication.

What are lake nutrients and why do they matter?

In freshwater science, lake nutrients usually refers to forms of nitrogen and phosphorus that algae and aquatic plants can use for growth. At low to moderate levels, these nutrients support a productive food web with phytoplankton, zooplankton and fish. Problems start when inputs from agriculture, wastewater or urban runoff push lakes beyond their natural balance.

A practical eutrophication definition is the gradual enrichment of a lake or reservoir with nutrients, leading to more algal biomass and shifts in oxygen conditions. At first, extra lake nutrients may just mean slightly greener water in summer. Over time, however, eutrophication can lead to dense blooms, murky water and low‑oxygen zones that stress fish and benthic organisms. The European Environment Agency reports that nutrient concentrations in many European lakes have improved over recent decades, but that phosphorus and nitrogen still remain too high in a significant share of water bodies.

The role of phosphorus in eutrophication

Because phosphorus is often the limiting nutrient in lakes, the phosphorus cycle plays a central role in how fast eutrophication develops. Phosphorus arrives with inflows, settles into bottom sediments and can later be released back into the water under low‑oxygen conditions. That internal recycling means a reservoir can keep reacting to past nutrient loads long after external inputs have started to fall. Guidance from the UK Environment Agency on phosphorus and freshwater eutrophication highlights phosphorus as the main driver of eutrophication in many freshwaters.

Source: Greenpeace International – “How can we restore Earth’s nutrient cycles?”

Eutrophication and how it changes lakes over time

Most textbooks describe eutrophication as nutrient enrichment that increases primary production and changes species composition. In the field, it shows up as more frequent algal blooms, reduced visibility through the water column and longer periods of low oxygen near the bottom. The EPA’s basic information on nutrient pollution notes that elevated nitrogen and phosphorus can double the likelihood of poor ecosystem health in lakes and rivers.

As nutrient availability climbs, fast‑growing algae out‑compete slower plants. Thick blooms form near the surface, blocking light from reaching submerged vegetation. When these blooms die, bacteria break down the organic matter and consume dissolved oxygen. In stratified lakes, this process can create low‑oxygen or even anoxic bottom waters that release more phosphorus from the sediment, feeding the next bloom and deepening eutrophication.

This feedback loop is one reason why managers pay so much attention to trophic state. Once internal loading becomes important, even a substantial cut in nutrient inputs may not improve water quality as quickly as communities expect. The USGS Lake Trophic State dataset uses satellite data to classify tens of thousands of lakes as oligotrophic, eutrophic or somewhere in between, illustrating how widespread nutrient impacts have become.

Lake nutrients, the phosphorus cycle and drinking water reservoirs

Drinking water reservoirs are especially sensitive to eutrophication because managers must balance ecological health with strict water quality standards. Warm, stable surface layers, combined with elevated nutrient concentrations, create ideal conditions for cyanobacteria. Some species produce cyanotoxins, so understanding how the phosphorus cycle interacts with stratification is essential for keeping supplies safe.

The World Health Organization’s drinking-water guidelines and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s nutrient policy pages both highlight eutrophication as a driver of taste, odour and treatment challenges in surface‑water supplies. They recommend systematic monitoring of chlorophyll‑a, nutrients and oxygen profiles to detect problems early.

In many reservoirs, managers now use buoy‑based platforms and shore stations as part of an online monitoring network. Continuous measurements of key variables help them see when the upper layer is warming faster than usual, when algae begin to respond to pulses of nutrients, and when low‑oxygen conditions might trigger additional phosphorus release from the sediment.

Source: Earth.com – Clear Lake turns green with algal growth (NASA Earth Observatory image)

Measuring lake nutrients and detecting eutrophication early

Monitoring programmes usually combine laboratory analysis of lake nutrients with in‑situ sensors for temperature, oxygen and algae. Grab samples tell operators exactly how much nitrogen and phosphorus are present, while continuous profiles show how stratification and mixing change the way those nutrients move through the water column.

Agencies such as USGS use long‑term data sets to study trends in eutrophication across thousands of lakes and reservoirs. Their work shows that reducing external loads does help, but that internal processes linked to the phosphorus cycle can slow recovery, especially in deep or strongly stratified systems.

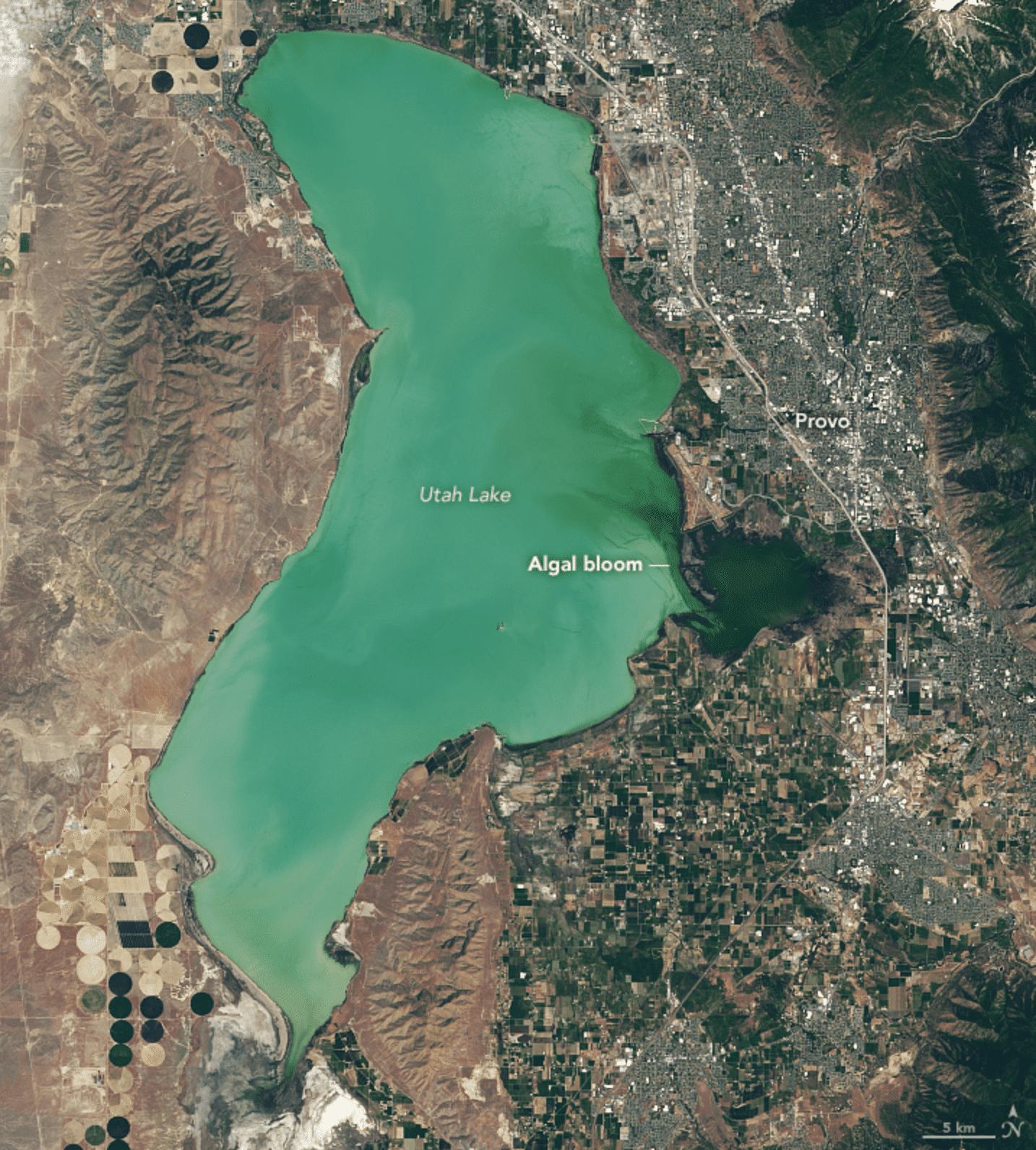

Remote sensing adds another layer. Satellite‑based products from programmes highlighted by NASA’s inland water quality training materials can map surface chlorophyll and turbidity over wide areas, helping to identify eutrophication hotspots that deserve more detailed sampling. Case studies on Utah Lake show how early detection of colour changes allowed health agencies to act days earlier than they could have using ground observations alone. See also NASA’s summary on early detection of algae blooms by satellite for more detail on this example.

Managing nutrient enrichment from catchment to reservoir

The best long‑term defence against eutrophication is to reduce the flow of nutrients from the surrounding catchment. This usually involves a combination of agricultural best practices, improved wastewater treatment and better stormwater management in urban areas. Wetlands and vegetated buffer strips can capture part of the nutrient load before it ever reaches the reservoir.

Because the phosphorus cycle has both external and internal components, managers usually plan for gradual change rather than instant results. They may, for example, pair catchment measures with in‑lake actions such as optimised withdrawal depths, aeration or other site‑specific tools that help maintain oxygen in bottom waters and slow internal phosphorus release. The EPA nutrient criteria technical guidance for lakes and reservoirs offers practical advice on setting targets that reflect local conditions and designated uses.

Clear communication with communities is also important. Explaining eutrophication in plain language, and showing how nutrient concentrations have changed over time, makes it easier for stakeholders to understand why measures in the wider catchment are necessary and why the visible response in the reservoir can take a while. Public‑facing fact sheets such as the Nutrient pollution overview from EPA can help support those conversations with non‑technical audiences.

Ultrasound-based control as part of an integrated strategy

While nutrient reduction tackles the root causes of eutrophication, many reservoirs also need tools that act on algae directly. LG Sonic applies low‑power ultrasound in combination with continuous monitoring to reduce algal biomass in lakes and drinking water reservoirs without adding chemicals to the water.

Buoy‑based systems measure chlorophyll‑a, phycocyanin, temperature and other variables, then adjust ultrasound programmes to local conditions. By limiting algae access to light and disrupting their position in the water column, these solutions help reduce the impact of high nutrient levels and slow down the visible symptoms of eutrophication. For an overview of how this works, see LG Sonic’s technology explanation.

In practice, ultrasound is used alongside catchment measures and careful monitoring of the phosphorus cycle. Real‑time dashboards allow operators to see how algal indicators respond over weeks and seasons, and to demonstrate to regulators and communities that the combined strategy is reducing bloom frequency and supporting a more stable reservoir. Case studies of large drinking water reservoirs using ultrasound‑based control are available on LG Sonic’s project pages.

Conclusion

Lake nutrients sit at the centre of many water quality challenges. When nitrogen and phosphorus inputs rise, the risk of eutrophication and harmful algal blooms increases, especially in warm, stratified drinking water reservoirs. Understanding the phosphorus cycle, applying a clear eutrophication definition and using good data all help managers make better choices.

By combining long‑term nutrient reduction in the catchment with continuous monitoring and ultrasound‑based control on the water, it becomes possible to keep nutrient concentrations at manageable levels and protect both ecosystems and drinking‑water supplies. Details always vary from site to site, but the overall message is simple enough: when we take eutrophication seriously and act early, lakes and reservoirs have a much better chance to recover.