Every day, millions of Americans turn on their taps, visit local beaches, or drink from private wells without realizing they may be exposing themselves to dangerous contamination. The growing threat of toxic waters represents one of our most pressing environmental health challenges, affecting both our drinking water supplies and the recreational waterways we depend on for swimming, fishing, and ecosystem health.

From blue green algae blooms that force beach closures to lead contamination in community water systems, the scope of water contamination extends far beyond what most people realize. Recent data reveals that unsafe levels of various contaminants affect water sources serving over 200 million Americans, with minority and rural communities facing disproportionate risks.

This comprehensive guide will help you understand the different types of toxic waters threatening our communities, recognize the health impacts of exposure, navigate the regulatory landscape, and take action to protect yourself and your family from contaminated water sources.

What Are Toxic Waters?

Toxic waters contain harmful chemical, biological, or physical contaminants that pose significant health risks to humans and wildlife. These dangerous substances can present in drinking water sources, recreational waterways, and groundwater systems across the United States, creating a complex web of contamination that affects millions of people daily.

The definition of toxic encompasses any water body where pollutants exceed safe levels established by health authorities. Unlike clean water that meets EPA standards, toxic waters contain a mixture of harmful substances including heavy metals, industrial chemicals, agricultural runoff, sewage overflow, and naturally occurring toxins like those produced by blue green algae. Current statistics paint a concerning picture of water quality nationwide. The EPA reports that over 9 million Americans receive drinking water from systems that violate federal safety standards. Additionally, researchers have documented widespread contamination affecting both surface water and groundwater sources, with some communities experiencing multiple types of pollution simultaneously.

Major Types of Water Contamination

Understanding the different pathways through which contamination occurs helps explain why toxic waters have become such a pervasive problem. Water systems face threats from multiple sources, each requiring different approaches for prevention and treatment.

Drinking water contamination affects both large community water systems serving cities and towns, as well as private wells that supply rural households. These sources face different regulatory oversight and testing requirements, creating significant variations in water quality across geographic regions. Surface water pollution impacts rivers, lakes, coastal areas, and other bodies of water used for recreation, fishing, and ecosystem functions. Unlike drinking water sources that typically receive treatment before reaching consumers, surface waters often receive direct exposure to pollutants from various sources.

Source: https://www.wateroam.com/water-facts/is-my-drinking-water-safe

Groundwater contamination presents unique challenges because underground aquifers can remain polluted for decades once contaminated. This type of pollution often results from industrial activities, agricultural practices, and improper waste disposal that allows chemicals to seep through soil into underground water supplies.

Drinking Water Contaminants

- Heavy metals are among the most dangerous substances in community water systems nationwide. Arsenic, naturally occurring in some geological formations, affects water supplies in all 50 states, with high levels reported in the Southwest and New England. Lead contamination, highlighted by the Flint Water Crisis, continues to impact hundreds of communities where aging infrastructure allows this toxic metal to leach into drinking water.

- PFAS, or “forever chemicals,” have been found in water supplies serving over 200 million Americans, according to recent EPA data. These synthetic compounds, used in products from non-stick cookware to firefighting foam, persist in the environment and accumulate in human tissue. The extent of PFAS contamination has led EPA to develop new testing requirements and consider stricter regulations.

- Agricultural runoff introduces nitrates into rural water supplies, often exceeding EPA limits. Primarily from fertilizer use and livestock operations, nitrates pose risks to infants and pregnant women. This issue worsens in areas with intensive farming, creating persistent groundwater contamination.

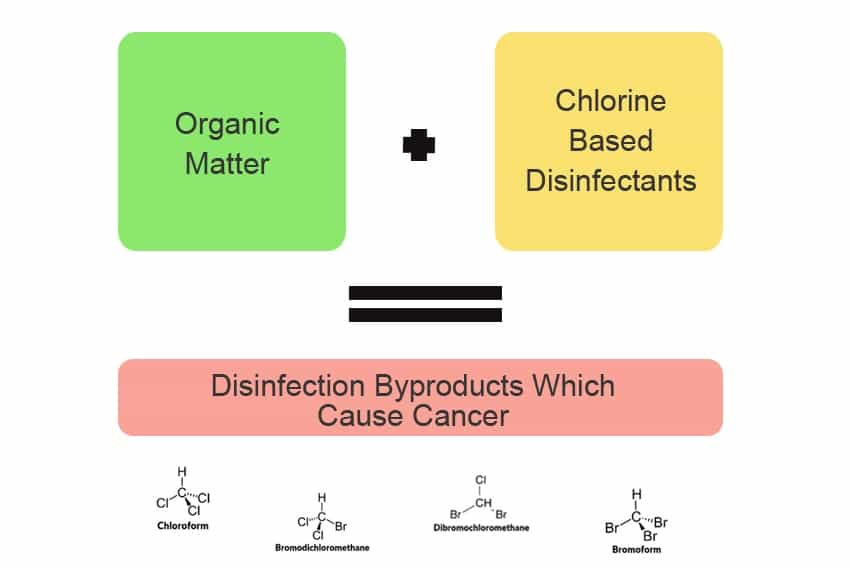

- Chlorinated disinfection byproducts form during water treatment when chlorine reacts with organic matter. While chlorination kills harmful bacteria and viruses, it creates chemical compounds that may increase cancer risk with long-term exposure. Water systems must balance disinfection needs with minimizing these byproducts.

Hence, drinking water in the U.S. faces persistent risks from metals, chemicals, and byproducts that demand careful monitoring and management.

Recreational Water Contaminants

Blue-green algae, scientifically known as cyanobacteria, create some of the most visible and immediately dangerous forms of water contamination affecting recreational areas. These organisms naturally occur in freshwater environments but proliferate rapidly under certain conditions, creating dense blooms that produce potent toxins harmful to humans, pets, and wildlife.

- The occurrence of harmful algal blooms has increased dramatically in recent decades, with factors including nutrient pollution, warm temperatures, and reduced water flow contributing to their development. Massachusetts reported at least 70 beach closures in 2023 due to blue-green algae outbreaks.

- Combined sewer overflow events release untreated sewage directly into waterways during heavy rainfall when treatment systems become overwhelmed. These overflows introduce pathogenic bacteria, viruses, and other contaminants that make swimming and other water contact activities dangerous for days or weeks following an event.

- Industrial discharge and stormwater runoff carry toxic pollutants from manufacturing facilities, urban areas, and transportation corridors into rivers, lakes, and coastal waters. This pollution includes heavy metals, petroleum products, and synthetic chemicals that accumulate in sediments and fish tissue, creating long-term contamination that affects entire aquatic ecosystems.

- The combination of these contamination sources creates complex pollution problems that require comprehensive monitoring and intervention strategies. Many waterways experience multiple types of contamination simultaneously, making it difficult to identify specific sources and develop effective treatment approaches.

Health Impact Due to Toxic Waters

The health consequences of exposure to toxic waters range from immediate acute illnesses to long-term chronic diseases that may not manifest for years or decades. Understanding these risks helps explain why water quality protection represents such a critical public health priority.

- Cancer risks from long-term exposure to arsenic, lead, and industrial chemicals found in contaminated water supplies affect millions of Americans. Arsenic, classified as a known human carcinogen, increases the risk of skin, lung, and bladder cancers even at relatively low concentrations. Epidemiological studies have linked chronic arsenic exposure to increased cancer rates in communities with contaminated groundwater, particularly in rural areas where private wells lack regular testing.

- Lead contamination in drinking water poses severe developmental risks to children, whose developing nervous systems are particularly vulnerable to this toxic metal. Even brief exposure to elevated lead levels can cause permanent cognitive damage, learning disabilities, and behavioral problems. The Flint Water Crisis demonstrated how quickly lead contamination can develop when proper corrosion control measures are not maintained in aging water distribution systems.

- Fatal effects on pets and livestock from algae toxin exposure serve as early warning indicators of dangerous contamination levels. Dogs, in particular, are vulnerable because they may drink large quantities of contaminated water while swimming or playing near affected water bodies.

Hence, veterinarians in areas with frequent algal blooms report increased cases of toxin poisoning in domestic animals, often with fatal outcomes.

Regulatory Framework and Priority Pollutants

The EPA’s Priority Pollutant List contains 126 toxic substances regulated under the Clean Water Act since 1977, providing the foundation for federal water quality protection efforts. This list includes heavy metals, pesticides, industrial solvents, and other chemicals known to pose significant risks to human health and aquatic ecosystems.

The Safe Drinking Water Act establishes maximum contaminant levels for public water systems, requiring regular testing and treatment to ensure water meets federal safety standards. However, these regulations only apply to community water systems serving 25 or more people, leaving millions of Americans who rely on private wells without mandatory testing or treatment requirements.

State-level regulations vary significantly in strictness across different jurisdictions, creating a patchwork of protection standards that can leave some communities vulnerable to contamination. Some states have adopted more stringent standards than federal requirements, particularly for emerging contaminants like PFAS, while others rely solely on federal minimums that may not address all local contamination sources.

Enforcement gaps allow continued contamination in vulnerable communities despite existing regulatory frameworks. The EPA has limited resources for monitoring compliance and pursuing enforcement actions against violators, particularly in cases involving diffuse pollution sources like agricultural runoff that are difficult to regulate effectively.

Geographic Hotspots and Vulnerable Communities

- Tribal lands experience disproportionate water contamination from uranium and other heavy metals, legacy of decades of mining and industrial activities on or near reservation boundaries. Many tribal communities lack access to adequate water treatment infrastructure and face regulatory challenges due to complex jurisdictional issues between federal, state, and tribal authorities.

- Rural communities relying on private wells face particular vulnerabilities because these water sources are not subject to the same testing and treatment requirements as public water systems. The EPA estimates that over 43 million Americans depend on private wells, many of which have never been tested for common contaminants like nitrates, bacteria, or heavy metals.

- Industrial corridors along major rivers like the Mississippi and Ohio experience multiple pollution sources from manufacturing facilities, chemical plants, and transportation activities. These regions often serve as sacrifice zones where environmental justice communities bear disproportionate exposure to toxic contamination while receiving limited protection from regulators.

- Environmental justice research has documented how communities of color and low-income areas are more likely to be located near contamination sources and less likely to receive prompt remediation when problems are identified. This pattern reflects decades of discriminatory land use planning and enforcement decisions that have concentrated environmental hazards in vulnerable communities.

The intersection of poverty, race, and environmental contamination creates compound vulnerabilities where affected communities often lack the political power and economic resources needed to advocate for cleanup and protection measures. These disparities persist despite federal environmental justice policies intended to ensure equitable protection for all communities.

Solutions and Water Protection Strategies

Stronger EPA enforcement of existing Clean Water Act provisions could significantly reduce contamination from point sources like industrial facilities and sewage treatment plants. The agency has authority to impose substantial penalties on violators and require comprehensive cleanup measures, but enforcement actions have declined in recent years due to budget constraints and political pressures. On 05 Aug 2025, EPA announced over $9 million in grant funding for midsize and large water systems to help protect drinking water from cybersecurity threats and improve resiliency for extreme weather events.

Enhanced monitoring and testing protocols for emerging contaminants like PFAS will help identify contamination sources and protect public health. The EPA is developing new testing requirements for community water systems and considering whether to regulate additional substances currently not covered by federal standards. Community-based water quality monitoring programs engage citizens in data collection and environmental protection efforts. These programs provide valuable information about local contamination problems while building community capacity to advocate for protection measures. Examples include volunteer monitoring networks that track algal blooms and citizen science initiatives that help identify pollution sources.

Pollution prevention through agricultural best practices and industrial discharge controls offers the most cost-effective approach to protecting water quality. Programs that help farmers reduce fertilizer and pesticide use, implement cover crops, and create buffer zones along waterways can significantly reduce nutrient and chemical runoff that contributes to contamination problems.

Technological innovations in water treatment, including advanced oxidation processes and membrane filtration systems, offer new tools for removing difficult-to-treat contaminants. However, these technologies often require significant energy inputs and produce concentrated waste streams that must be properly managed.